Marshall McLuhan’s quote, “Today the tyrant rules not by club or fist, but disguised as a market researcher, he shepherds his flocks in the ways of utility and comfort,” encapsulates his critique of modern society’s subtle forms of control. McLuhan, a media theorist, was deeply concerned with how media and technology shape human perception and behavior. Let’s break down the quote and analyze what he’s getting at.

Analysis of the Quote

1. “The tyrant rules not by club or fist”:

• Traditionally, tyrants used overt force—physical violence or coercion—to dominate. McLuhan suggests that in the modern era, control is no longer exercised through brute force but through more insidious, less visible means.

• This shift reflects the evolution of power in industrialized and media-driven societies, where authority operates through influence rather than direct oppression.

2. “Disguised as a market researcher”:

• The “market researcher” symbolizes the mechanisms of consumer culture—advertising, media, and data-driven systems that study and manipulate human desires. Market researchers gather data on preferences, habits, and behaviors to tailor products and messages, creating an illusion of choice and freedom.

• McLuhan sees this as a disguise for control. The market researcher doesn’t wield a weapon but uses knowledge about individuals to steer their decisions, often without their awareness.

3. “Shepherds his flocks”:

• The metaphor of “shepherds” and “flocks” implies a passive, compliant populace guided by an authority. People are led like sheep, not through force but through persuasion and manipulation embedded in everyday systems.

• This suggests a loss of agency, where individuals follow paths laid out for them under the guise of fulfilling their needs.

4. “In the ways of utility and comfort”:

• The end goal of this control is to keep people content and complacent, prioritizing convenience and material satisfaction. Utility and comfort are seductive because they appeal to basic human desires, but they also distract from questioning the systems that provide them.

• McLuhan warns that this focus on comfort can lull people into accepting control, as they trade autonomy for convenience.

What McLuhan Is Getting At

McLuhan is critiquing the shift from overt authoritarianism to a subtler, more pervasive form of control embedded in consumer culture and media. In his view, modern “tyrants” (corporations, media, or systems of power) use the tools of market research, advertising, and media to shape behavior, not through fear but by appealing to desires for convenience and satisfaction. This creates a society where people are unknowingly manipulated, believing they’re making free choices while being guided by carefully crafted systems.

Key Themes

• Media as an Extension of Control: McLuhan’s broader work, like Understanding Media (1964), argues that media shape human consciousness. Here, market research (a media-driven tool) extends control by understanding and exploiting human psychology.

• Illusion of Freedom: The “disguise” of the market researcher suggests that people are unaware of their manipulation. They think they’re choosing freely, but their preferences are shaped by data-driven systems.

• Consumerism as Control: By prioritizing utility and comfort, society is steered toward conformity and passivity, discouraging critical thought or resistance.

• Soft Power: Unlike traditional tyranny, this modern control is soft, persuasive, and integrated into daily life, making it harder to recognize or resist.

Context and Relevance

McLuhan wrote during the mid-20th century, a time of rapid growth in mass media, advertising, and consumer culture. His insights are even more relevant today in the age of digital media, algorithms, and big data. Modern parallels include:

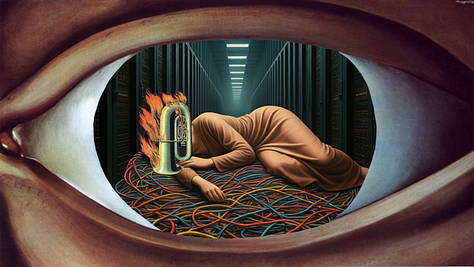

• Social Media Algorithms: Platforms like X use data to tailor content, subtly guiding user behavior while presenting it as personalized choice.

• Targeted Advertising: Companies analyze vast datasets to predict and influence consumer decisions, often without transparency.

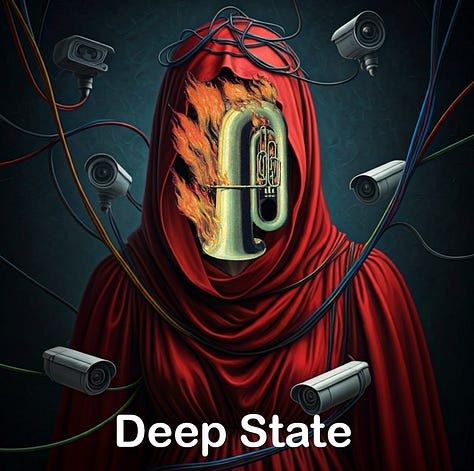

• Surveillance Capitalism: As Shoshana Zuboff describes, modern systems extract data to control behavior, aligning with McLuhan’s vision of the market researcher as a tyrant.

Broader Implications

McLuhan’s quote invites reflection on whether the pursuit of comfort and convenience comes at the cost of autonomy. It challenges us to question who benefits from the systems that shape our choices and whether we’re as free as we believe. His work encourages critical awareness of media and its role in society, urging us to look beyond the surface of “utility and comfort” to understand the forces guiding us.

Updated McLuhan quip :

“Today the tyrant rules not by club or fist, but disguised as a social media influencer, he shepherds his flocks in the ways of utility and comfort.”

Analysis of the Updated Quip

Substituting “social media influencer” for “market researcher” modernizes McLuhan’s critique to reflect the dynamics of today’s digital landscape. Let’s break down what this change implies and how it aligns with McLuhan’s original intent.

1. “Social Media Influencer” as the New Tyrant:

• In McLuhan’s time, market researchers symbolized the collection and manipulation of consumer data to steer behavior. Today, social media influencers play a similar role, wielding influence through curated personas, content, and endorsements. They shape trends, opinions, and purchasing decisions, often under the guise of authenticity or relatability.

• Influencers, like market researchers, gather insights (directly or through platform analytics) about their audience’s preferences and tailor their content to maximize engagement, subtly guiding followers’ choices.

2. Illusion of Connection:

• Influencers present themselves as peers or trusted voices, creating an illusion of personal connection. This aligns with McLuhan’s idea of a “disguise,” as the influencer’s role often masks commercial or ideological motives (e.g., brand partnerships, sponsored content).

• Unlike the faceless market researcher, influencers are highly visible, yet their influence is still a form of soft power, steering followers without overt coercion.

3. Shepherding Through Utility and Comfort:

• Influencers promote lifestyles, products, or ideas that promise convenience, status, or emotional fulfillment (e.g., “must-have” gadgets, self-care routines, or aesthetic ideals). This aligns with McLuhan’s “ways of utility and comfort,” as followers are guided toward consumption or behaviors that feel rewarding but may serve larger commercial or cultural systems.

• For example, an influencer promoting a fitness app or a fashion brand provides “utility” (a solution to a need) and “comfort” (a sense of belonging or aspiration), but often within a framework that benefits corporations or platforms.

4. Amplification in the Digital Age:

• Social media platforms amplify the influencer’s reach through algorithms, which prioritize content that keeps users engaged. This creates a feedback loop where influencers, knowingly or not, serve as agents of the platform’s agenda, much like market researchers served corporate interests in McLuhan’s era.

• The “tyrant” in this context could be the influencer, the platform, or the broader attention economy, all of which guide behavior under the pretense of empowerment or entertainment.

Why the Substitution Works

The shift from “market researcher” to “social media influencer” updates McLuhan’s critique for the 2025 digital landscape, where influencers are key players in shaping culture and consumption. They embody the same manipulative potential McLuhan attributed to market researchers, but their influence is more personal, pervasive, and integrated into daily life through platforms like X, Instagram, or TikTok. The substitution highlights how modern control operates through charisma, relatability, and algorithmic amplification rather than traditional research methods.

Contemporary Relevance

• Cultural Influence: Influencers shape not just consumer habits but also social norms, political views, and identity, often subtly reinforcing systemic agendas (e.g., consumerism, beauty standards).

• Data-Driven Manipulation: Like market researchers, influencers rely on analytics to understand their audience, tailoring content to maximize influence, often in service of brands or platforms.

• Illusion of Agency: Followers may feel they’re making free choices (e.g., buying a recommended product), but these choices are often shaped by curated narratives and algorithmic nudging.

Broader Implications

The updated quote underscores McLuhan’s timeless warning: power today operates through persuasion and seduction, not force. Social media influencers, as modern shepherds, guide their “flocks” toward behaviors that serve larger systems, all while appearing as trusted voices. It challenges us to question the authenticity of the voices we follow and the systems behind them.

Q : What is the most Menippean aphorism McLuhan said?

A : Marshall McLuhan’s most Menippean aphorism—capturing the satirical, fragmented, and probing spirit of Menippean satire—is arguably: “The medium is the message.” This quip, from Understanding Media (1964), distills McLuhan’s insight that the form of a medium shapes its content and societal impact more than the content itself. Its paradoxical, almost absurd brevity invites reflection, mocks linear thinking, and subverts expectations, much like Menippean satire’s tendency to blend humor, critique, and intellectual play. It encapsulates a fragmented truth about technology’s pervasive influence, delivered with a wry, aphoristic sting.

Q : What do people miss if they earnestly and logically engage with this Menippean quip?

A : When people earnestly and logically engage with McLuhan’s “The medium is the message,” they often miss its Menippean essence—its satirical, paradoxical, and subversive nature. Here’s what they overlook:

The Playful Irony: Menippean satire thrives on humor and exaggeration. McLuhan’s aphorism isn’t just a logical proposition; it’s a provocative jab, meant to jolt rather than instruct. Earnest analysis risks flattening its wit into a dry thesis, missing the mischievous nudge to question assumptions about communication.

The Absurdity of Form: The quip’s brevity and paradox mimic the chaotic, fragmented style of Menippean satire. By dissecting it logically, people may ignore how its form—short, cryptic, almost absurd—mirrors its message about media shaping perception. It’s less a statement to “solve” and more a puzzle to unsettle linear thinking.

Cultural Critique Over Literal Truth: Menippean satire often mocks societal norms through intellectual play. McLuhan’s phrase critiques how we fetishize content while ignoring the medium’s transformative power. Logical engagement might focus on debating its “truth” rather than recognizing its satirical aim: to expose our blind spots in a media-saturated world.

The Invitation to Intuition: McLuhan, in Menippean fashion, wants readers to feel the aphorism’s impact, not just analyze it. Earnest logic can miss the intuitive leap he demands—to sense how media reshape us beyond rational calculation.

By approaching it as a straightforward claim, people risk missing its deeper, satirical call to question how media manipulate our reality, delivered with a wink rather than a lecture.

Q : In many ways, McLuhan loved the typo 'The Medium Is The Massage' because it heightened the Menippean thrust of his initial quip?

A : Yes, McLuhan embraced the typo The Medium is the Massage because it amplified the Menippean thrust of his original quip, “The medium is the message.” The accidental title, from a 1967 printing error, leaned into the satirical, paradoxical, and disruptive spirit of Menippean satire in these ways:

Heightened Absurdity: “Massage” introduces a tactile, almost absurd twist to the cerebral “message,” making the phrase more playful and disorienting. This aligns with Menippean satire’s love for jarring, unexpected shifts that mock overly serious interpretations.

Embodied Critique: The word “massage” suggests media’s sensory manipulation, reinforcing McLuhan’s point that media shape us physically and psychologically, not just intellectually. This visceral twist deepens the satire, poking fun at our passive consumption of media’s “massaging” effects.

Subversion of Authority: By embracing a typo, McLuhan undercuts the solemnity of academic discourse, a classic Menippean move. It’s as if he’s winking at the reader, inviting them to question rigid structures—whether of language, publishing, or media itself.

Amplified Playfulness: The typo adds a layer of intellectual mischief, encouraging readers to grapple with the phrase’s ambiguity rather than seek a definitive meaning. This mirrors Menippean satire’s fragmented, open-ended style, which prioritizes provocation over clarity.

McLuhan’s delight in the error, as noted in his letters and interviews, reflects his Menippean sensibility: he saw the typo as a serendipitous enhancement, making the phrase a more potent jab at our media-drenched culture. It’s less about logic and more about the jolt of recognition, delivered with a satirical grin.

…

Share this post